The news headlines at the beginning of 2002 the made for dire reading: “Phylloxera Hits New Zealand’s Fastest-Growing Wine Region” read Wine Spectator. This was indeed bad news for the Central Otago wine region which was growing rapidly due to sudden international popularity of it’s Pinot Noir wines. Perhaps too rapidly, as only 55% of vines had been planted with Phylloxera resistant plants.

While the emergence of Phylloxera in Central Otago was bad news it was no surprise. In fact, there is a saying in wine making that there are only three certainties in life: death, taxes and Phylloxera.

WHAT IS PHYLLOXERA?

We need to go back 160 years to the 1850s to understand the story of Phylloxera. Modern wine as we know it comes from a plant called Vitis Vinifera – in layman terms European grapes. When English botanists travelled to the US they discovered a vine growing there also – Vitis Riparia. Although the wines were not great, the theory was they would bring these vines back to Europe and try them there – maybe with better winemakers and viticulturists they would produce better grapes capable of making better wines.

Little did they know, that as well as vines, the English were bringing with them another unwanted immigrant. Vitis Riparia carried with it a vicious aphid, an aphid that had no effect on the American vines, but loved their European cousins, attacking their roots and sucking them quickly to death. The aphid, Phylloxera, spread rapidly across Europe, destroying nearly all vines in it’s path over a period of about 30 years.

The fight to combat Phylloxera took grape growers to both extreme methods such as burying a toad beneath the vines to draw out the poison, or unscrupulous production methods of mixing in all sorts of different juices and concoctions. By the end of the 19th Century. at a more sensible level. the cross pollination of American and European plants had become the most popular solution. However, unfortunately the subsequent wines that these plants produced were relatively unpalatable and omitted a strong odour.

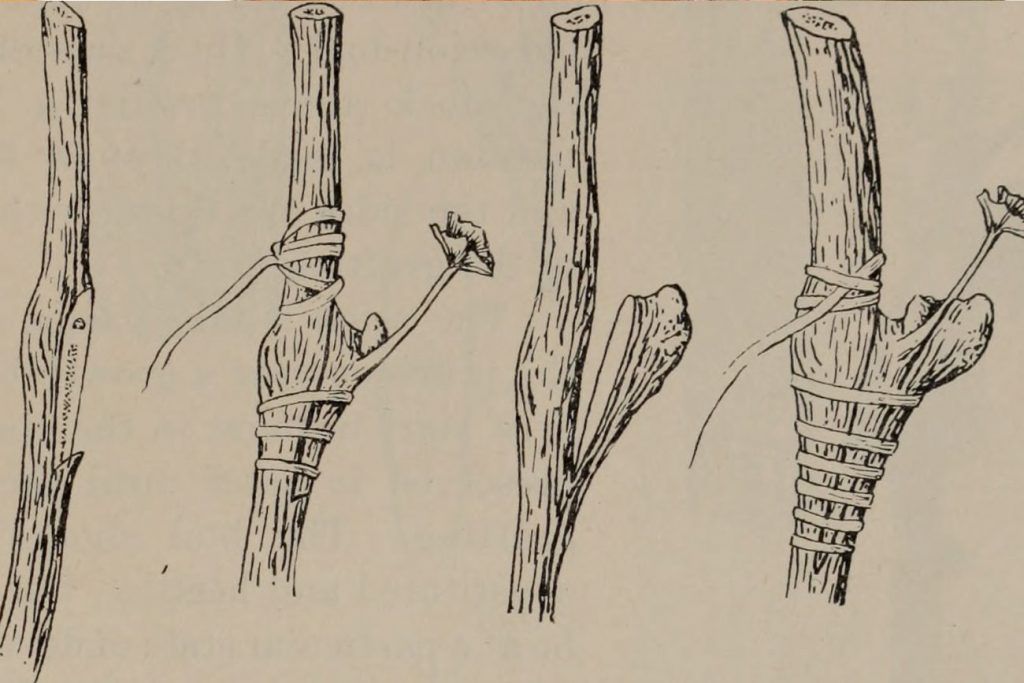

In the early twentieth century a botanist by the name of Charles Valentine Riley came to the rescue making a discovery that was to become the solution indefinitely. Riley grafted American Vitis Riparia rootstock onto European Vitis Vinifera creating a plant that had immune roots and drinkable fruit. The solution was found and in the majority all vines were replaced.

WHAT WENT WRONG IN CENTRAL OTAGO?

There are two corollaries to that story. The first being a discovery that Phylloxera does not travel well through heavy sand or schist soils. Some of the grapes in Europe were spared and even today there are pockets of vines that are still 100% Vitis Vinifera such as the Riesling in the slate soil of the Mosel Region in Germany, wines grown on the sand in Provence, a Spanish wine with a particular micro-climate. plus a tiny parcel of Pinot Noir used in rare Bollinger champagnes (Oh, how I would love some of that about now!).

The second exception to the story is one of pure economics. In fact, in the US, a clone of one type of US root stock called AxR1 was planted simply because it was cheaper, and despite many objections, after a number of years the Phylloxerid aphid mutated and began to destroy the plants. The US vineyards were forced to replant – the same exercise Central Otago has been going through.

Like the US example, the Central Otago story comes pretty much down to cost. The rapid growth of popularity of Pinot Noir in the 1990s led to a bit of a gold-rush, with vineyard plantings and the cost of planting un-grafted vines, plus the time required often outstripping the alternatives by quite some margin. Plus, at that stage Phylloxera was nowhere to be seen and many believe Central Otago’s schist and sandy soils might mean the vines would be spared those in Mosel, Western Australia and other special cases. Unfortunately, by early 2002 we knew this was not to be the case.

In modern times the presence of Phylloxera is nowhere near as devastating as it was for the Europeans in the 19th Century. The vines actually keep producing for up to ten more years with no impact at all on the taste of the wine while the aphids suck away, and with good vineyard management a period of transition to grafted vines is both economical and achievable.

While you are on your wine tours in Gibbston Valley you will notice two things. Firstly, the presence of many signs on Phylloxera free vineyards warning of the movement of plant and materials between vines. On the other hand you will also see rows of vines that are clearly effected and very slowly shriveling away. It is very interesting as the vineyards manage the economics of having the vines continue to produce grapes for wine with the economics of replanting.